On a Women’s Expedition, Cliona learns about the realities of menstruation in some parts of Nepal – and meets the women working to change the narrative.

I bury my face in a pile of still-warm T-shirts and leggings as I sort through my freshly washed laundry. Nothing beats the sweet, soapy scent of clean clothes after a week of trekking.

As I shake out the last of the bag, a pair of period undies falls on the floor. I pick them up and hold them out in front of me. They look familiar. My size. But they’re not mine. So I send a quick message to the group chat:

‘Morning! Is anyone missing a pair of black period undies? I picked them up in the launderette in Pokhara.’

It’s no big deal. Just a mix-up. But a few days later, I’d see that stray pair of underwear in a whole new light.

I’m on Intrepid’s Women’s Expedition in Nepal – a trip designed to let travellers experience the country through the eyes of local women. So far, we’ve listened to morning prayers at Kapan Ani Gompa – a Buddhist nunnery where women have a rare opportunity to receive a traditional monastic education; we’ve learned how to make momos with a lovely lady named Dolma who was born and raised in a Tibetan refugee camp; and we’ve danced to Shakira’s Waka Waka with our all-female trekking crew under a full moon in the Annapurna foothills.

My period just so happened to coincide with the trek. Typical, I know. Given the choice (if only), I would’ve picked another week. But I had painkillers at the ready, a hefty stock of Snickers and a group of brilliant women by my side. It was a slight inconvenience, but it wasn’t going to stop me.

But when we return to Kathmandu and visit an NGO called Days for Girls, I learn that getting your period goes far beyond inconvenience for some Nepali women.

Banished for bleeding

We pull up outside a building on the busy street of Bafal Marg. There’s a sign reading ‘turning periods into pathways’ above the door. Motorbikes zip past in an endless stream, and while I linger for a gap in the traffic, our leader, Keshu, strides out with an open palm, bringing the bikes to a halt. I shuffle behind her like a duckling.

Waiting to greet us is Maya Khaitu, the country director of Days for Girls Nepal. The organisation is a part of a global non-profit working to eliminate stigma and limitations around periods. Through community education and sustainable period products, the NGO is improving the health and livelihoods of girls and women in Nepal, Kenya and Guatemala, among other countries.

‘Watch your heads,’ Maya warns as we climb a narrow metal staircase to a small classroom where we’ll learn more. Two team members hand out small bouquets of powder-pink amaryllis flowers to each woman in our group as we settle into our seats. Although the windows are shut, there’s no escaping Kathmandu’s soundtrack of honking horns and yapping dogs.

‘As you know,’ Maya says, ‘menstrual health is stigmatised.’ I see a wave of nodding heads in the corner of my eye. ‘But in far western and midwestern Nepal, women and girls are banished to cattle sheds or makeshift huts during their period.’

‘And just two months ago,’ she continues, ‘a woman was attacked by a tiger while she was sleeping in one of these sheds.’

The street noise dissolves like sugar in a cup of masala chiya, and a collective gasp sweeps through the room.

This practice of isolating women on their period is part of chhaupadi, a centuries-old tradition where menstruation is seen as impure.

The tiger fled after villagers raised the alarm, Maya told us. The woman survived with minor facial injuries, but some aren’t so lucky. More recently, a woman tragically died from a snake bite in a menstrual shed in Kanchanpur.

This practice of isolating women on their period is part of chhaupadi, a centuries-old tradition where menstruation is seen as impure. During their bleed, women aren’t allowed to stay in the home or do everyday tasks like cooking and cleaning – or even touch others – out of fear they’ll bring death, illness, crop failure or some other bad luck to the family.

The huts, known as chhau goths, have poor sanitation and ventilation, and women face many dangers including wild animal attacks, freezing temperatures, smoke inhalation and sexual assault. Unfortunately, many sexual assault cases go unreported due to social stigma and lack of adequate support systems.

Maya tells us that in the past, women would sleep in a cave or an open field – even in the rain or snow. ‘Some older women have said, “Oh, these girls are so lucky staying in a cow shed!” – because sometimes all they had was a basket filled with hay to scatter and sleep on.’

When we ask Maya how the women feel about chhaupadi, she says it’s complicated.

‘Because girls are indoctrinated about the beliefs surrounding menstrual impurity from a young age, there’s often a blend of social conditioning and willing participation due to fear of spiritual repercussions if they break the rules. It can be tricky to distinguish genuine belief from reluctant compliance.’

Life-changing period kits

The Nepali government outlawed chhaupadi in 2005 and has tried to destroy the huts, but it often continues due to deep-rooted taboo and superstition.

‘The government provides free pads, but they often run out fast and are poor quality. And they don’t always provide education and alternative solutions to chhaupadi, so that’s where we step in,’ Maya says.

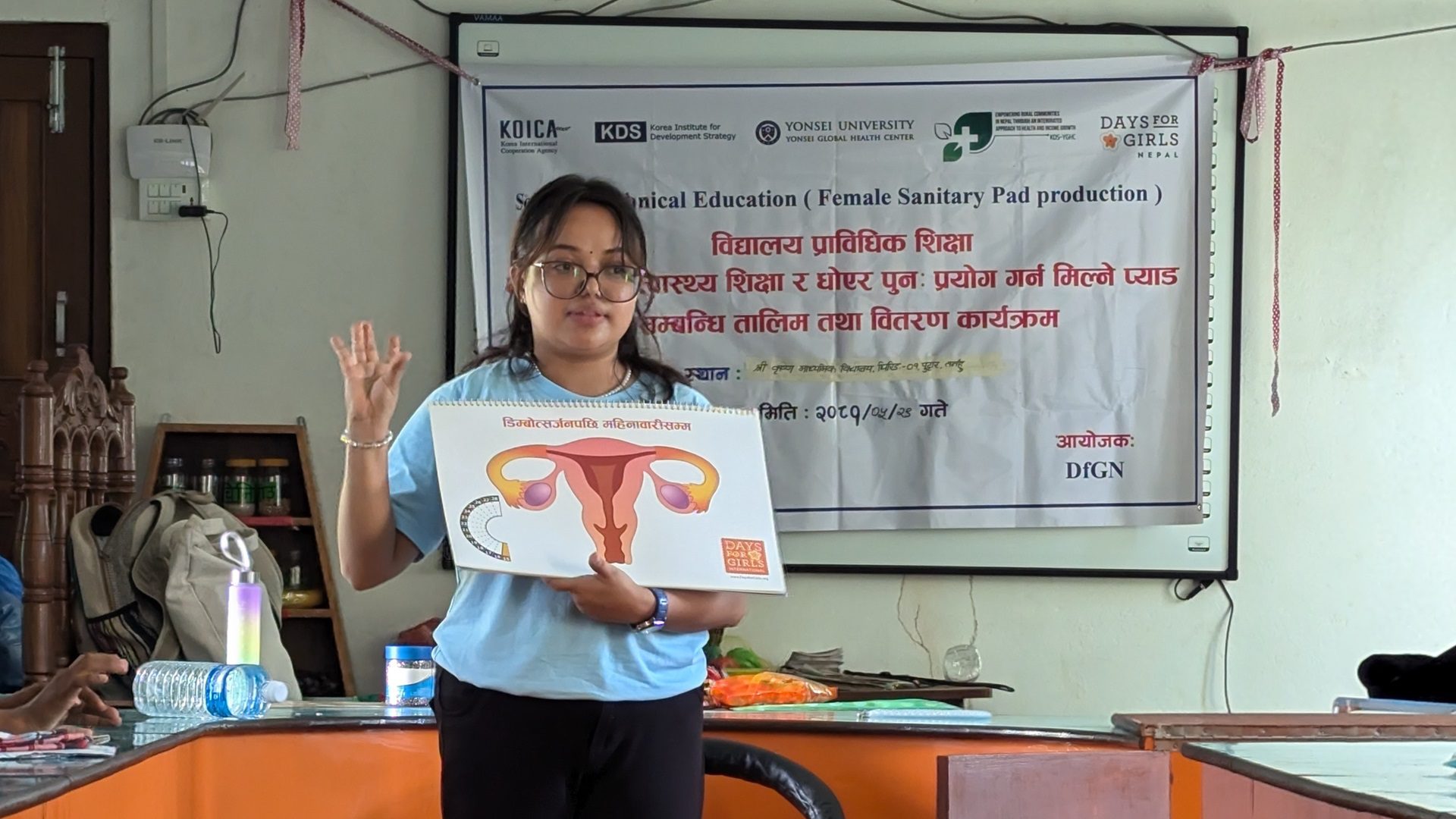

Working with local authorities, Maya and her team deliver workshops and period kits around the country.

The kit includes a workbook on everything from reproduction, consent and sexually transmitted infections to human trafficking and child marriage. (Like chhaupadi, child marriage still continues despite the government increasing the legal age to marry from 18 to 20 in 2017.) Through menstrual health education, they find it easy to spark wider conversations about women’s safety.

‘We talk about the changes that happen during puberty, as we want to prepare preteens to talk confidently about their problems, concerns and how they feel. And when we hold women’s circles, we talk about menopause too,’ Maya says.

The kit also contains a cycle-tracking calendar and specially designed reusable sanitary napkins – patented by Days for Girls and made in-house. I can hear the faint click-clack of sewing machines downstairs.

‘During the training, we show them how to wear the napkins – and it’s not like this!’ she says, smiling as she pulls it over her jeans to demonstrate how some women think they go over their saris.

The napkins are beautifully designed with bright colours and bold patterns – at first glance, they could pass for a small coin purse. But what strikes me is how nifty they are. Each set comes with a protective water-resistant shield (secured with snap-buttoned wings) and a few absorbent liners that slot inside and can be tri-folded to suit your flow. They wash easily, dry quickly and last for up to three years.

‘When I was younger,’ Maya reflects, ‘we didn’t have pads, so we had to scrunch up old cloth. I was scared to run or walk, but with these, you can jump, dance, do anything you want! It gives you freedom.’

She tells us that even women in Kathmandu, who can afford and access disposables, are buying these kits as they’re better for the environment.

Read more: What it’s like on a Women’s Expedition in India

Education is everything

Since 2016, Days for Girls Nepal has reached over 65,500 women and girls with their pad kits and education sessions. School absenteeism has reduced as a result, and they have helped create income opportunities by training women to make and sell pads in their communities.

Because ending period stigma involves everyone, they’ve also had over 2000 men and boys join their Men Who Know program.

‘Many boys and men are genuinely interested in understanding menstrual health and want to support the women in their lives. After the sessions, their perception of periods often shifts from one of taboo or misunderstanding to one of empathy and awareness.’

On a few occasions, Maya mentions that their approach is not to tell communities what to do. Instead, they hope their workshops help people make informed decisions about whether to continue chhaupadi, based on a deeper understanding of health, safety and human rights.

Collecting data on entrenched cultural practices is challenging, but around 90 per cent of families in Kalikot, Manma, Sipkhana, Mumra and Siuna now allow women and girls to sleep in separate rooms at home instead of sending them to chhau goths.

‘It will take a while, step by step, but things are slowly changing through education.’

Read more: An Intrepid trip inspired me to uproot my life and move to Morocco

From stigma to strength

As we climb into the minivan and fasten our seatbelts, Maya and her team – the women turning periods into pathways – lean over the balcony railings, waving us goodbye.

I think about the times I’ve been doubled over with cramps, but in the comfort of my own home, with a hot water bottle and a cup of tea. I think about the products available to me – the fact that I can buy them with my own money and without shame. And I think about the stigma that still lingers, all over the world, around something as normal and universal as periods. Hard to believe, really, given that half the global population experiences it as some point in their lives.

Those forgotten undies from the laundry mix-up might not have been mine, but they represented freedom for a woman to live, move and do what she wants, even when she’s bleeding. A freedom not all women have. And one I’ll never take for granted.

‘Our message is to let girls know that menstruation is powerful and beautiful,’ Maya told us. ‘The uterus is your first home, and if menstruation is impure, then everyone is impure. That’s where we start. It’s simple!’

It’s a simple truth in a complex world, and one this NGO is on a mission to share – one conversation and period kit at a time.

Cliona travelled on Intrepid’s Nepal: Women’s Expedition. The cost of the trip includes a donation to Days for Girls, so by travelling with Intrepid, you’ll be supporting the organisation’s important work.