Writer Liisa Ladouceur travels to North Africa for a new experience with Intrepid to meet a master calligrapher in his studio and learn the significance of this skilful script.

The pen makes a squeaking sound as I move it across the page from right to left. ‘Again’, I’m gently encouraged. Just a few more tries until my hand creates a solid mark of brown ink deemed the right size and shape. It looks like a simple oversized dash, but it’s the first step in learning to write my name in fancy Arabic script. I feel a swell of pride at my tiny accomplishment. My hand repeats the move, this time working from top to bottom. ‘Voila’, says the instructor. ‘Now, we can work.’

I’m in a traditional dar (house) in the historic medina of Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, learning the art of Arabic calligraphy.

My teacher is Hamza Chebbi, a 30-something fine artist and painter with a warm demeanour and soft voice, who practises calligraphy every day. I, while a lifelong writer, have never had what one could call great penmanship. But I’ve long admired the grace and glamour of calligraphy.

Read more: 26 totally new Intrepid trips and experiences

Falling in love with letter writing

I’m the kind of traveller that still sends physical postcards home. I romanticise the days when we still took our time with things like writing letters. But where I’m from in Canada, even writing by hand is becoming a lost art.

Here in Tunisia, where Arabic calligraphy dates back centuries, I find practitioners like Hamza are keeping this beautiful form of writing alive. On my Premium Tunisia trip with Intrepid, I would come to notice it everywhere, from mosques and museums to its modern interpretation – a blend of calligraphy and graffiti, known as ‘calligrafitti’ – in the streets.

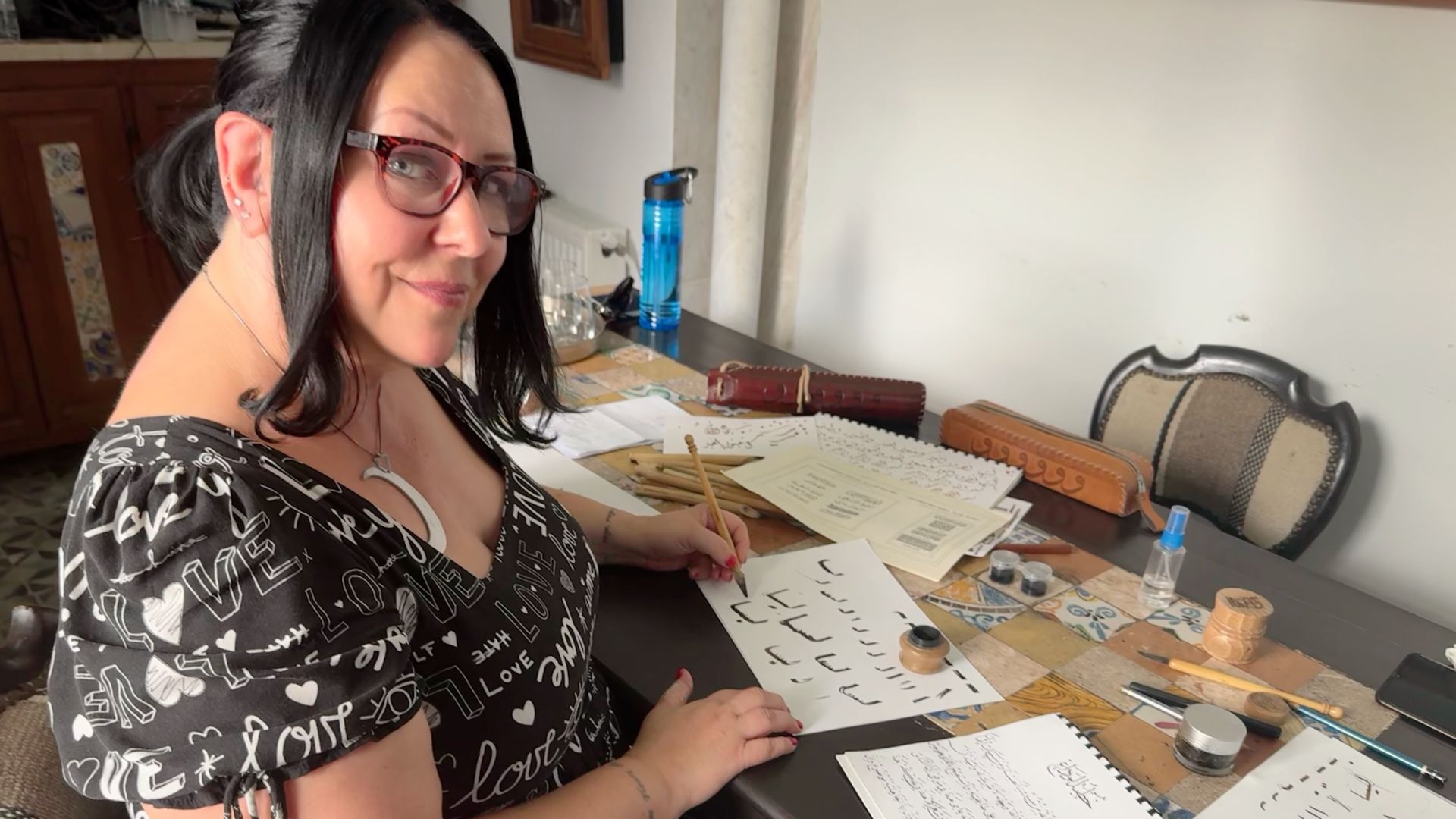

But first, the lesson. On the table in front of us, Hamza spreads out his calligrapher’s tools. Small pots of special ink, he explains, are made with silk fibres – easy to transfer and quick to dry. We use the brown one, his favourite colour.

There’s also stack of simple pens, handmade from bamboo. He passes me one and I feel a tinge of nervousness. I’ve held pens my whole life, but this one feels more like chopsticks, awkward in my hands. Like a good yoga teacher giving a slight adjustment to your posture, he rotates the pen and guides the angle until I have it just right. I stab the nib into the inkwell and place it on the smooth white paper. Squeak, squeak. Slowly, with much laughter and humility, I find a flow.

Read more: 10 new cultural craft experiences

Cultural kudos from UNESCO

There are 47 different styles of Arabic calligraphy, Hamza tells me, opening his notebooks filled with exquisite texts written in the geometric Kufic, elaborate Thuluth and elegant Diwani variations.

He first picked up the Diwani style while studying art at university in the coastal town of Nabeul, about 70 kilometres south of Tunis on the Mediterranean Sea. ‘When I was a kid, I was always making sketches and drawing. When I learnt we could use it not only to write or read, but to use the shapes to make paintings and graphic art, that’s when I fell in love with calligraphy.’

I like the Diwani style, with its decorative flourishes. Hamza tells me the origins are Ottoman, from the 16th century, then points upward to a stunning metal light fixture and explains that the symbol etched in Diwani calligraphy is the Arabic word for ‘light’. Ah, brilliant.

Then I notice a repeating pattern carved into the white walls that surround us. Before, I might have mistaken this as a trellis of leaves, or pure abstraction, but now know it’s the 99 names of Allah, a signature of Arabic design and architecture.

It’s this mix of tradition and modernity that helped put Arabic calligraphy on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2021.

‘That’s opened many doors for calligraphy, to introduce this art that’s been going around 1600 years to the world’, says Hamza. ‘I’m proud of it’.

Read more: 9 new trips and experiences in Africa

A script that spans centuries

The roots of Arabic calligraphy are practical – a writing technique created to record important Arabic language texts, such as the Qur’an. Over time, artists developed new styles and innovated motifs to use in all kinds of mediums, from embroidery and wood carving to abstract art and graffiti.

Today, a talented calligrapher can make good living creating logos, signage, wedding invitations and book covers. I ask Hamza if it is taught to young people in schools, either for creativity or as a career prospect, and am surprised to learn that it’s not. He says he’s working to change that, developing a curriculum for elementary schools as well as these classes for curious adults.

‘It’s not only about writing,’ he says, of his love for teaching. ‘It’s about sharing; it’s the connection in the moment. You don’t need to know how to read it to feel it.’

As we work on my class assignment, we talk about art. Arabic calligraphy is practised in many countries, including Morocco, Lebanon, Egypt and the UAE, but Tunisia can boast many of the world’s most famous calligraphers. Like painter Nja Mahdaoui, an award-winning legend considered the inventor of abstract calligraphy; or muralist and sculptor eL Seed, whose large-scale street art has been displayed around the world, from the pyramids of Giza to the duomo in Milan.

‘You know Cubism? Realism?’ Hamza asks. ‘We have Lettrism’. He shows me some of his own paintings, a series which uses the shapes of the 28 letters from the Arabic alphabet, freed from their linguistic constraints, to create individual everyday scenes. I realise I’ve seen Arabic calligraphy in art and architecture for a long time but never had the context for this visual language which being here in Tunisia and talking to a local artist brings.

Awakened to a new cultural language

I get into a groove and finally do manage to spell ‘Liisa’ in Arabic calligraphy: a symmetrical ‘swoosh’ with four small teeth and two dots below. It’s not perfect, but I think it’s pretty. Hamza also presents me with his professional version: a beautiful gift.

Exiting the dar onto the narrow streets of the medina, I spot my first calligraffiti on the side of a building under construction. I realise my lesson hasn’t just earned me a new skill and souvenir. It’s offered me a different window into Tunisia’s culture.

Later, when our group visits the city of Kairouan, I remember Hamza teaching me about the Kairouani style of calligraphy, used in important religious texts. In the Bardo Museum in Tunis, when I spot pages from the famed 9th-century Blue Qur’an, which many scholars believe originated in this country, I appreciate the pride in which Tunisians take in displaying it. And in the seaside streets of Sidi Bou Said, I look beyond the picturesque blue doorways to seek out street art, where calligraphy is used to display the public sentiments of the day. I can’t read any of it, but I can understand that in this country with such a rich history, the story continues to be written.

Master calligraphy on Intrepid’s Premium Tunisia adventure and find out what else is new for 2026 with The Goods – a collection of new trips and experiences to inspire a year of adventure.