In Amman’s oldest neighbourhood, Jabal al-Weibdeh, you’ll find Beit Sitti (translation: my grandmother’s house). Up a set of brightly coloured stairs, it’s equal parts cooking school and social experiment, run by three sisters who are integrating food, culture, women’s rights, and conversation into one delicious, thought-provoking afternoon on a sun-drenched sandstone rooftop.

They say the best way to truly connect with a culture is through its food, and in the case of Jordan, this couldn’t ring truer. Through sharing and making traditional meals and drinks while enjoying conversations with the locals, you’ll fall in love with the people, mystique, and undeniable magnetism of this peaceful Middle Eastern country.

TAKE A COOKING CLASS AT BEIT SITTI ON ONE OF THESE SMALL GROUP ADVENTURES IN JORDAN

Up the stairs to Beit Sitti.

Bleary-eyed after a 24-hour journey from Vancouver, Beit Sitti was my second stop after a morning spent wandering Amman’s bustling streets and markets full of produce and spices, sipping sugarcane juice, and sampling habiba kunafa (a local staple) with my friendly local guide Mustafa Orabi. I visited the same market the sisters frequent to stock up on fresh ingredients for their classes; stalls lined with pomegranates the size of small watermelons, piles of almonds still in their fuzzy green shells, more types of dates and olives than I knew existed, and eggplants that resemble footballs.

EXPLORE OUR FULL RANGE OF SMALL GROUP ADVENTURES IN JORDAN HERE

Fuzzy-skinned almonds in the market.

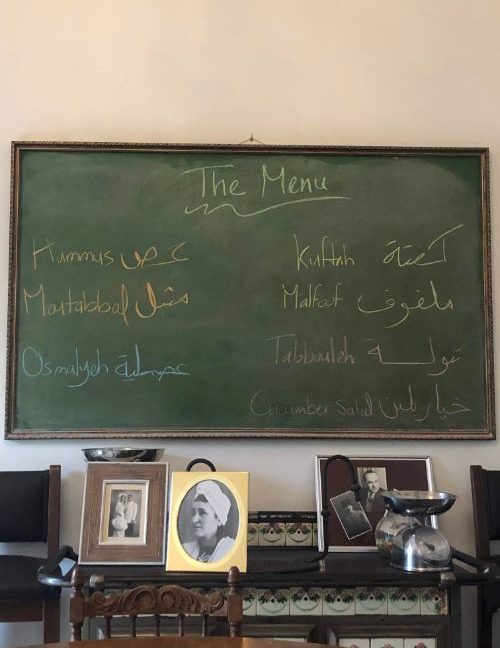

The inside of Beit Sitti – the old limestone house Maria Haddad Hannania and her sisters Dina and Tania grew up learning to cook in – is just as their grandmother left it, filled with dozens of old family photos, and original antique furniture, including a Singer sewing machine and an old wood-burning stove. Two women tinker in the simple kitchen, where copper pots and pans are hung on the wall and an orange fridge contrasts beautifully with the dark green cabinetry filled with every spice imaginable. Across the room, intricately hand-painted plates hang from the wall, and a couple of large dining tables are draped with old lace tablecloths.

What we‘re cooking.

As we begin our class and go over the menu of what we’re about to make – maaloubeh, mouttabal, fattoush salad, and traditional Arabic bread – it quickly becomes apparent that this experience is about much more than the food.

The whole idea of Beit Sitti is to create a platform for communication between the guests and the cooks in a setting where they’re able to talk freely. “We know there’s a lot of things that people from abroad want to ask about, such as the hijab, Islam, fasting, or how Muslim men can marry three wives, that in most other situations might not be appropriate to ask,” says Maria. “The women in our kitchen are very happy answering these questions.”

RELATED: HOW A LAST-MINUTE TRIP TO JORDAN SAVED MY CAREER

Whipping up a storm in the Beit Sitti kitchen.

“People in the West sometimes think that women in Jordan are not treated equally, or they don’t have a say, but when they can have a conversation with a woman in a hijab and understand that it’s her choice, it makes a big difference,” she adds.

Beit Sitti employs all local women, a concept frowned upon in Jordanian society until Queen Rania stepped in with equality campaigns that helped promote the importance of education and including females in the workplace.

“A lot of the women, at first, were ashamed to come to work with us. For them it was shameful to work and try to support their husbands and families,” she says, not referring to the younger generation of university-educated women, but to the generation of uneducated women who were raised during a time when families could only afford to send the men to school. “Slowly, we’re seeing a shift and women are saying ‘No, I want to come work and I want to make money for my family’.”

A delicious cucumber and tomato salad.

Beit Sitti now has five women on call to teach classes. The cooking school creates a space for working-class women from all around the region, not just Jordan. “We have a Syrian woman, a Palestinian woman, an Iraqi woman, and a Jordanian woman. Each of them makes the dishes that their country is most well-known for,” adds Maria. My chefs for the day are Um Reem from Iraq, who’s been working with the sisters for nine years, and Um Tia, who came from Syria at a very young age and married a Jordanian man.

RELATED: WHAT TO EXPECT AS A SOLO FEMALE TRAVELLER IN JORDAN

They’ve had an incredible amount of interest as word spreads, but since the space is small they’ve started teaching women in different regions of Jordan how to make the pomegranate molasses, za’atar, tahini, and mixed spices and stock used in their classes and available for purchase. “We go to their homes and offer them work instead of them coming to us.”

Technically, Jordanians aren’t allowed to employ refugees or anyone without a Jordanian passport, but that hasn’t stopped Maria. “A lot of them leave their families and they don’t have anyone, so we become like their family.”

Beit Sitti.

The food choices are of equal cultural and political importance as the conversation.

“We teach people how to make Arabic food. It’s not Jordanian food – there’s no such thing as just ‘Jordanian food’ because of all the influences that came with the refugees from Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon 70-100 years ago,” she says. “Syrians say it’s Syrian, Palestinians say it’s Palestinian, Jordanians say it’s Jordanian, Lebanese say it’s Lebanese – it’s Arabic; there’s no specific place because the region is so small. The borders were essentially open a long time ago, it was really just one country, so all the food is similar.”

Though the dishes have subtle variance between regions, at Beit Sitti they stick with their grandmother’s original recipes, enhanced by expert tips from the local women. “We’ve learned that adding a little cardamom uplifts the flavour of the maaloubeh, for example,” she adds.

The hot tip for creating the perfect mouttabal is charring the eggplant until it’s burnt, Um Tia says. We leave ours over a flame grill for half an hour, rotating it while preparing the other ingredients. Once charred, we let the eggplant cool for 10 minutes, and then gently peel off the blackened skin and set it aside. We chop up the smoky eggplant and mix it with lemon juice, garlic, tahini, and yogurt, then garnish with salt, sumac, parsley, and olive oil. Um Tia gently guides my hand to perfect my knife skills, so that I don’t squish the eggplant too much, the same way she later shows me how to knead the dough for the bread and squeeze out the perfect-sized ball of dough to be flattened with a dash of olive oil.

Charring the eggplant.

Then we begin working on the main course – maaloubeh – which translates to ‘flipped upside down’. Many Arabic dishes are named by the way that they are cooked. This dish is layered like a cake in a large copper pot; it has eggplant, marinated in salt, fried cauliflower, chicken boiled in a special stock mix, tomatoes, rice, onion, and spices. As the name alludes to, once it’s cooked you have to flip it upside down onto a plate, slowly lifting the pot, revealing what is supposed to look like a cake.

As I swiftly flip over the pot and place it upside down on a plate, Um Tia urges me to make a wish as I tap the top and side, ensuring none of the ingredients get stuck. Nervously, with all eyes awaiting the result, I reveal a perfectly intact maaloubeh.

As the sun begins to set and the call to prayer echoes across the neighbourhood, we head outside to the terrace to enjoy our meal. Looking out over Jabal al-Weibdeh, drenched in a misty, golden light that turns the sandstone buildings a dusty orange colour, I’m surrounded by laughter and applause for a job well done.

I offer my guide, Mustafa, some of my leftovers to take home; I’m travelling solo and couldn’t possibly eat the entire thing myself in the next 24 hours. Using his hands, he scoops up a few bites, exclaims how impressed he is, then eats a bit more. He laughs, and explains there’s no way he could possibly bring another woman’s cooking home to his wife – something that is surely going to change in Jordanian culture soon.

So, it is true, that the purest way to get to know a new culture is in the kitchen. Not only is being in the kitchen at Beit Sitti an incredible food experience, but it’s also a window into Arabic culture – specifically into the world of Arabic women. It’s there in the kitchen at Beit Sitti that women are liberated – free to talk about their past, how they came to Jordan, and share their plans for the future.

Months later, I’m here at home feeling grateful for this experience. I still have my fingers crossed the wish I made that day, while tapping the maaloubeh pot, comes true. That inshallah, one day I can make my way back to Jordan, for a pure, unfiltered exchange like this, that changed my perspective on Middle Eastern culture and set up the rest of my experience in Jordan with a full, open heart.

Interested in learning to cook traditional Arabic dishes at Beit Sitti? Explore our range of tours through Jordan now.

All photos by Alicia-Rae Olafsson.